The Cost of Empty Bookshelves: Kyle Zimmer, First Book President, Co-founder, and CEO

Empty bookshelves in school libraries, kids without backpacks or lunch or socks, educators shelling out an average of $500 a year to outfit their classrooms–this is why we do what we do at First Book. And this year, we have the opportunity to make sure that every back-to-school start is a great start: full bookshelves, full backpacks, fully-outfitted classrooms. Here’s how you can help:

- If you’re an educator serving children in need, register with First Book.

- If you want to help make a difference for teachers heading back to school, click here to donate to First Book. Through September 6, 2018 a $3 gift will provide 2 books to a child, thanks to a generous group of donors who will match every donation.

The following post first appeared on Medium, April 20, 2018. Authored by Kyle Zimmer, president, co-founder, and CEO of First Book.

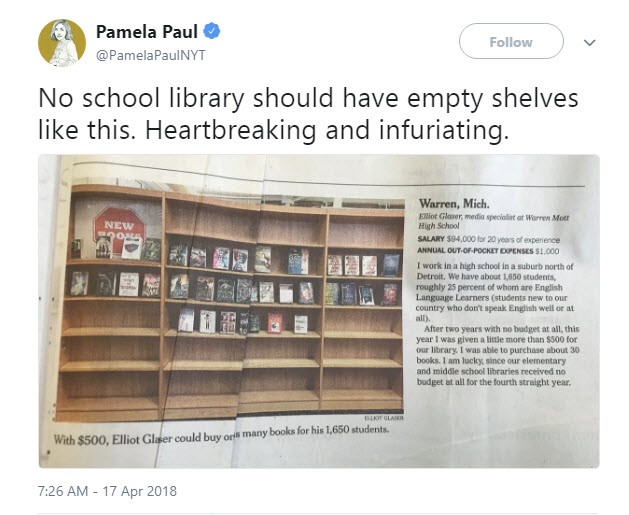

Pamela Paul is right. No school library should have shelves that look like this.

But too many school library shelves look just exactly like this. It is more than counter-intuitive — it’s harmful. Countless studies demonstrate that access to books and resources is the number one contributor to academic success in the United States. We also know that poor educational outcomes are tied to future poverty, unemployment, illness, and crime. And these factors disproportionately affect kids from low income households, who now account for more than half of all students in U.S. public schools.

We’re setting ourselves up to lose an entire generation of kids based on their ZIP code. Now is when we decide if that’s something we can live with.

I, for one, cannot.

Twenty-five years ago, some friends and I launched First Book as nonprofit social enterprise to tackle the issue with a systemic and sustainable solution. First Book’s market-driven models make brand-new, high quality books and resources affordable to educators serving kids in need. Through relationships with publishers, we created a marketplace stocked with more than 6,000 diverse and inclusive books and resources for free or at the lowest prices we can negotiate. We dedicate staff time to recruit funding from individual donors, corporate partners and other funders to defray costs — because too many schools and programs serving kids in need have no budgets for books and resources. Today, we have distributed 175 million books and reach five million kids each year through a network of more than 375,000 educators who exclusively serve Title I or Title I-eligible schools and programs serving kids in need. We grow by 1,000 educators a week.

That growth number alone is a testament to the need, and to the fierce dedication of the educators in our public schools and programs.

This is what it takes when the system stops working. We disrupt it with a solution that tackles the problem head-on. But we have much more to do.

Here’s what we know: 29 states are spending less per student than they did before the recession. Let me say that again so it sinks in: 29 states are spending less per student than they did before the recession. Right now, public school libraries and classrooms, especially in low income neighborhoods, are woefully under-supplied. And without budgets for books, a basic tool for learning, and other classroom supplies, more than 70 percent of our educators are spending money out of their own salaries to provide learning materials for the children they serve. Last summer, a teacher was begging for money on the side of the road to outfit her classroom.

Now teachers across the country are letting us know they can’t do it on their own anymore. This week’s New York Times story, “25-Year-Old Textbooks and Holes in the Ceiling: Inside American’s Public Schools,” provides a snapshot of what our educators face. Like Beth from Palacios, Texas. “In our supply closet, it’s rare to find tape and you’ll never find construction paper. Seeing my classroom would lead people to think things are great because my room is well supplied. It is. By MY paycheck.” Beth spends $2,000 each year out of her own pocket on school supplies for the kids she teaches.

I can think of no other profession where we ask trained, talented professionals to work in substandard conditions — offices with leaks, broken chairs and desks — require them to buy their own basic supplies or go without the tools they need, and still expect them to work miracles. Even super heroes need basic tools and supplies to do their jobs.

Have no doubt that educators are super heroes. They are the ones who, in spite of larger and larger classroom sizes, too often with outdated or no supplies provided, try not only to teach, but to address the needs of hungry kids without coats, socks and other basics, who are also traumatized by chronic stress.

It is too much to ask of our teachers. It is irresponsible and it is unacceptable.

This is where we have to step in if we are invested in our children’s future — and our own futures. Because the repercussions of staying our current course will impact us all.

This is a call to action. Our country’s educators are asking for support. Our children are marching for books, not bullets. What will you do?