Pride, Books, and More with TFA’s Tim’m West

With Pride Month already in full-swing, we recently had the chance to speak with Tim’m West, Senior Managing Director of Teach For America’s LGBTQ Community Initiative.

With Pride Month already in full-swing, we recently had the chance to speak with Tim’m West, Senior Managing Director of Teach For America’s LGBTQ Community Initiative.

We wanted to share his insights on advocating for and supporting LGBTQ youth, both inside and outside of the classroom. Tim’m’s years of experience working as an educator and youth advocate in the LGBTQ space means he can speak to just about any issue a teacher or educator might face when navigating what can be a delicate topic.

You currently have an excellent role with Teach for America. Tell us a little bit about the breadth of your experience in this space.

I’ve taught in three cities, some post-secondary, but mostly secondary, even mixes of college and high school. Beyond being a teacher and having the ability to bring an innovative ELA curriculum to institutions like Cesar Chavez School in DC, and Oakland School for the Arts in Oakland, I’ve always thought outside the box in terms of the types of literature that can be brought in. As a classroom instructor and a curriculum developer at heart, I find that opportunity really exciting. I think what’s as exciting, however, is the work that I’ve done in public health, LGBTQ youth development spaces.

Prior to coming to TFA, I was Director of the Youth Services Center on Halsted which is Chicago’s LGBTQ Youth Center and the largest LGBTQ Youth Center in the Midwest. We saw hundreds of kids over the course of a year, many of whom came from Chicago’s South and West sides, anywhere between the ages of 14 and up to 24… so, young adults, but also high school-aged kids. I’ve also worked in similar spaces like the Fusion Project in Houston, Texas, and the Evolution Project in Atlanta, Georgia. These kinds of LGBTQ youth groups are often under-resourced.

Everywhere I’ve been I made it a point to try to develop a library system. I’ve reached out to people that I’ve known personally— you know, “do you have books donate?”

I just find that, in particular for low-income, LGBTQ, youth of color, it’s really hard to find books that reflect their experiences.

Even if they have a school library, certain kinds of works that deal with LGBTQ identity or inclusiveness are just not available or may even be banned. It’s been a personal mission of mine to change that in the spaces where I’ve worked. It’s tough, to put it lightly.

At TFA, one of our priorities is creating partnerships between our alumni networks and various organizations to help build up literacy resources. The idea is to have our alumni in Memphis working with organizations like MAGY (Memphis-Area Gay Youth) to help them develop Prism (TFA’s regional LGBTQ affinity network) libraries so kids can have access to books. And I can say the same thing about Jacksonville, Florida and an organization called JASMYN. It’s just exciting how we can potentially leverage this broad network of teachers to help bring resources to kids that otherwise wouldn’t have access to those books.

It’s awesome to hear examples of all the great work happening, partially in the classroom but also meeting kids where they live through the healthcare space, the advocacy space, libraries, community programs, or through coalition building programs. Great suggestions for folks that might be working with kids in other capacities.

One thing about First Book that excites me is seeing that you’re not just acting in formal academic classroom spaces or schools. I think for the LGBTQ community in particular– in certain spaces certain books are banned and it’s hard to get access. The LGBTQ youth centers offer space where kids can have access to books they may not be able to in their schools. We deal with a lot of young people who are not out to parents. So even accessing a book at school, if it was available, comes with a certain risk. It’s a very real thing so I think the ability for kids to come to a center and get access to a book that’s appropriate and age-appropriate, is so critical and so important.

When you add books to these spaces, how does that impact the way kids see themselves or feel about themselves? And their peers?

I think it’s so critical to a child’s emotional development— people talk a lot about social emotional learning these days. Imagine being an LGBTQ youth in a space where your identity is never affirmed or when it comes up it’s talked about in a very negative way.

The importance of providing spaces where young people from low-income areas can come and get affirmation in their identity – strengthened by intersections where First Book is making books available — cannot be overstated.

Personally, I remember a teacher pointing me to a James Baldwin book. At the time, I don’t think I even understood they were aware I might be queer. This was a long, long time ago, but they made a point of pointing me to James Baldwin, maybe in a safe way, to say “do your own research and you may feel a connection.” I didn’t get it at the time, and I don’t think Giovanni’s Room was the best book for a struggling, closeted high school kid to read.

There’s a lot going on in Giovanni’s Room.

It’s such a tragic romance, I was just like, Is this what I have to look forward to? Falling in love and tragedy? When educators say, “Here are some books,” I think there’s an opportunity to be thoughtful and consider guidance that prepares students for the books they’ll read. It’s not just about building a library. I think this is one of the challenges that can come up: educators needing some guidance as they introduce books. I’d be interested in working with First Book to create some guidelines and curriculum ideas for teachers and educators.

How can sharing not only physical books, but even just stories about LGBTQ youth or families or experiences, help educators start conversations with their students?

One of the things I think about is the diverse family structures that our young people come from. There’s always been a common narrative of the mom, the dad, and the kids. That can be dis-affirming for a lot of low-income youth who have diverse family structures. I think having conversations about two moms, or two dads, or one dad or whatever, present opportunities for us to affirm all kinds of differences.

I’m thinking that And Tango Makes Three is one example that kind of comes to mind. In spaces where that kind of book could be presented to bring awareness—great. I think we are challenged in the current political landscape to think about how we make those kinds of stories available. Let’s say we can’t read And Tango Makes Three at a particular school: how can we take books that don’t explicitly talk about LGBTQ identity or family structures and create conversations about how it is a book about traditional families? How can we use that to bridge the gap and open up conversations about different kinds of family structures? I think there’s a certain creativity that must be there in certain spaces. As a curriculum developer and educator, I’ve always said, “give me a book and I will find a way.”

I’m thinking that And Tango Makes Three is one example that kind of comes to mind. In spaces where that kind of book could be presented to bring awareness—great. I think we are challenged in the current political landscape to think about how we make those kinds of stories available. Let’s say we can’t read And Tango Makes Three at a particular school: how can we take books that don’t explicitly talk about LGBTQ identity or family structures and create conversations about how it is a book about traditional families? How can we use that to bridge the gap and open up conversations about different kinds of family structures? I think there’s a certain creativity that must be there in certain spaces. As a curriculum developer and educator, I’ve always said, “give me a book and I will find a way.”

Can you tell us a little bit more about the training programs that you do? What’s going to be coming up at the Institute or the content of the training that you do for new TFA members?

So TFA’s LGBTQ Initiative started with me. There were efforts, small efforts, being made in a lot of our regions to bring attention to these issues but the initiative didn’t launch until October 2014, so we’re coming up on our third year. Interestingly enough, the anniversary is on National Coming Out Day, so what better a day to celebrate?

One of the things I found when I came to TFA is that there’s no true set of norms. Between our corps members and alumni, we have a network of well over fifty thousand. We have at any given time upwards of eight thousand corps members on the ground teaching across the country.

This is the first summer where all of our national institutes are doing the same training on supporting LGBTQ corps members and students. That’s not going to hit everywhere because we do have regional Institutes, some of them that I’m advising, but it’s a huge step in the right direction. We want to ensure that our corps members are getting a consistent message about things like intersectionality between race, class, and sexual orientation. There are teachers who are working in states where they could be fired legally if they are out, if they identify as LGBTQ, and so even helping support them and doing this work in a way that’s going to be safe for them is so critical and important.

We talk about how one navigates their own identity and the importance of allies. Through these trainings allies begin to understand there’s a certain privilege that comes with their identity. A straight, married guy advocating for safer spaces for LGBTQ youth, doesn’t come with the same risk as someone who self-identifies as LGBTQ. It’s important to just say; we need both our allies and people who courageously self-identify as LGBTQ working on this stuff. I think building a network that exists beyond just the corps experience is going to be critical going forward.

What barriers do you hear most often from educators who want to have conversations about identity or advocacy with their students but might be hesitant?

I think you named some of them. Ally-ship sounds really great conceptually, but what does that mean? How does it show up? One of the things that TFA does well is encouraging others to think about their own identity in critical ways. Who am I as a racialized person? As a gendered person? As a person with a sexual orientation? And how am I navigating my identity in relation to the students that I serve?

It shows up in all kind of ways. If you’re an African-American corps member teaching on a reservation in South Dakota, which I’ve seen and supported, what does it mean to be in that space? For some of those students you’re the only African-American person they’ve interacted with. What does it mean to be a South Asian corps member in the Mississippi Delta? So, we ask people: what does it mean to bring your full self to the classroom? How can you pivot from your personal identity in a way that is still affirming to students from different backgrounds and experiences?

I think one of the barriers for some people is that they haven’t had a lot of exposure. They just don’t want to mess it up, don’t want to get it wrong, and, on top of that, don’t want to get in trouble. I think the default thinking for a lot of our teachers is that it could get messy.

We did a workshop on how queer teachers could support LGBTQ students when they can’t be OUT. It was literally like, “this is how you work around the system.” So, for our allies, for our corps members that self-identify, it becomes a question of: how do we creatively think about it? How do we take mainstream, canonical pieces of literature and find ways to affirm our students inside of something that wasn’t necessarily intended to?

I think for me, as a poet and a writer myself, that’s the beauty. That’s the beauty of work, you get to bring something to it. You get to bring your identity to it.

Why is it important for all kids, regardless of their race or orientation or class to read stories about LGBTQ families or LGBTQ kids?

It’s important because it’s the world that we live in. I think the reality is even if there is one kid in that school who identifies as transgender, for example, the ability for that kid to have a safe and affirming education is dependent upon other people being aware of that identity and knowing how to respect it.

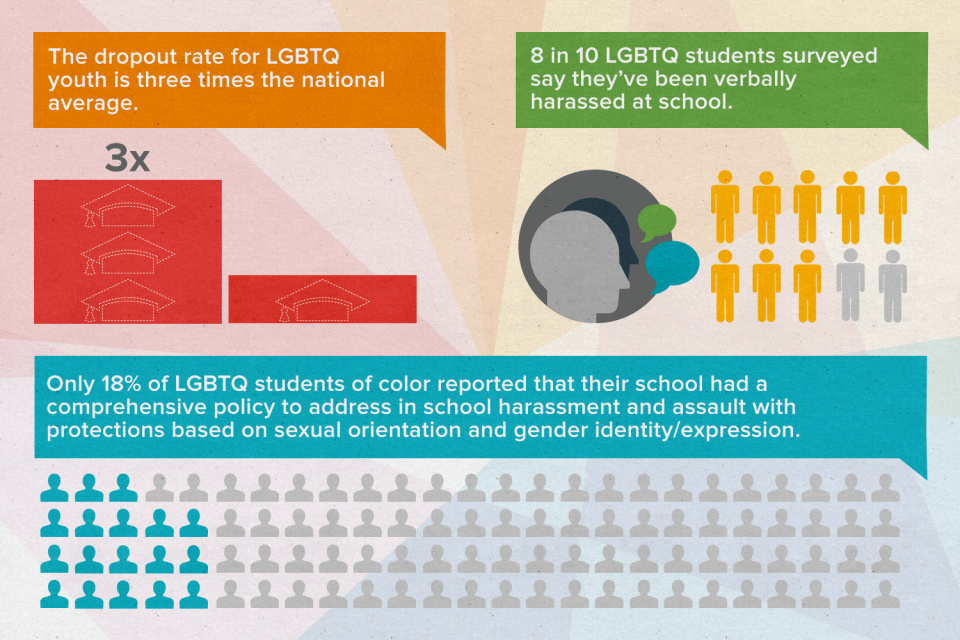

If we look at this through the lens of educational equity, it’s not simply about identity, it’s about the ability to provide all our students with a quality education and examining whether someone’s identity is a barrier in accessing that education.

When you think about it in that way, this is entirely an educational equity issue. What if there were somebody at each school who could introduce books that affirmed these kids, that made them feel like they were welcome? And just as importantly, somebody educating those kids who bully others because they don’t understand. I don’t think it’s always intended to be malicious. I think people can’t respect and affirm what they don’t know.

I think about my experience as a classroom teacher when I taught at the Cesar Chavez School in D.C., a relatively progressive area, but not so much in certain spaces. I was the only OUT queer teacher (to my knowledge) at Chavez when I was there. Students who would regularly make little homophobic comments came to know me and respect me and would shut each other down and be like, “hey, that’s not cool. It’s not cool to say that.”

Then all of a sudden, other kids start saying, “well actually I have two moms and I’m glad that you’re here because I can actually have space to talk about how my family is different.” I think that it’s just so important, just to build the awareness of the people who don’t self-identify so that they do learn to respect difference. It’s not about making everyone agree on identity, but it is to say that it shouldn’t be a barrier to people getting an education.

First Book is excited to partner with Teach For America’s LGBTQ Community Initiative to launch the newly formed “Brave Educators Book Club,” which kicks off on June 14, 2017.

The “Brave Educators Book Club” aims to:

- Bring together book lovers to discuss fun, engaging titles for all ages and;

- Build tangible skills by reflecting on how to engage and support LGBTQ students in your classroom and/or community.

Register for Brave Educators Book Club updates here!

With Pride Month already in full-swing, we recently had the chance to speak with Tim’m West, Senior Managing Director of Teach For America’s LGBTQ Community Initiative.

With Pride Month already in full-swing, we recently had the chance to speak with Tim’m West, Senior Managing Director of Teach For America’s LGBTQ Community Initiative.